March 2023

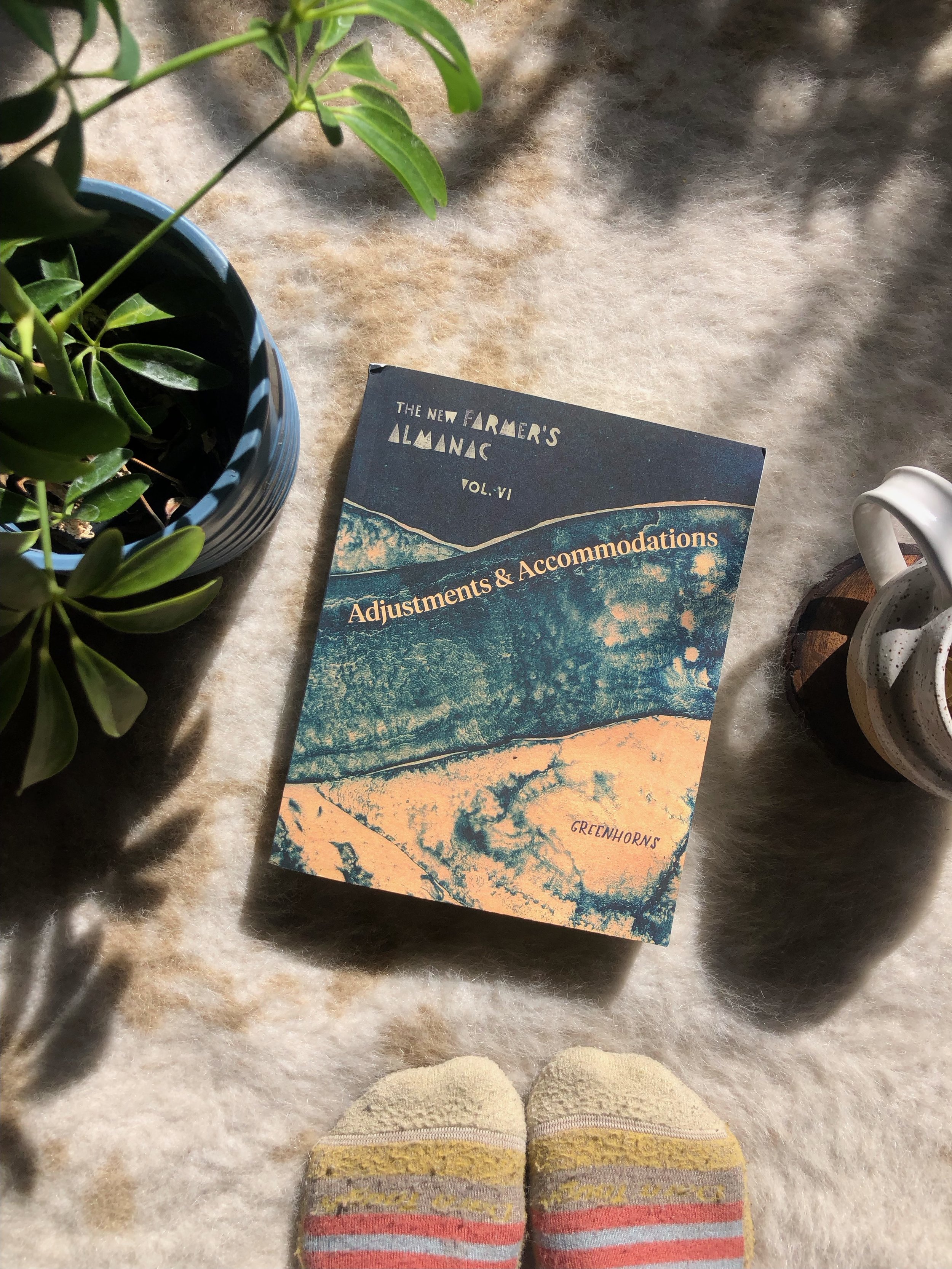

Honored to be published in the Greenhorns New Farmer’s Almanac Vol. VI “Adjustments & Accommodations” alongside such incredible contributors and reflections

“Adjustments & Accommodations humbly generates ideas and conversation around radical climate adaptations, cooperative farming, democratic economics, toxicity & regeneration, and the boom & bust energetics of a season on the land.”

- Greenhorns

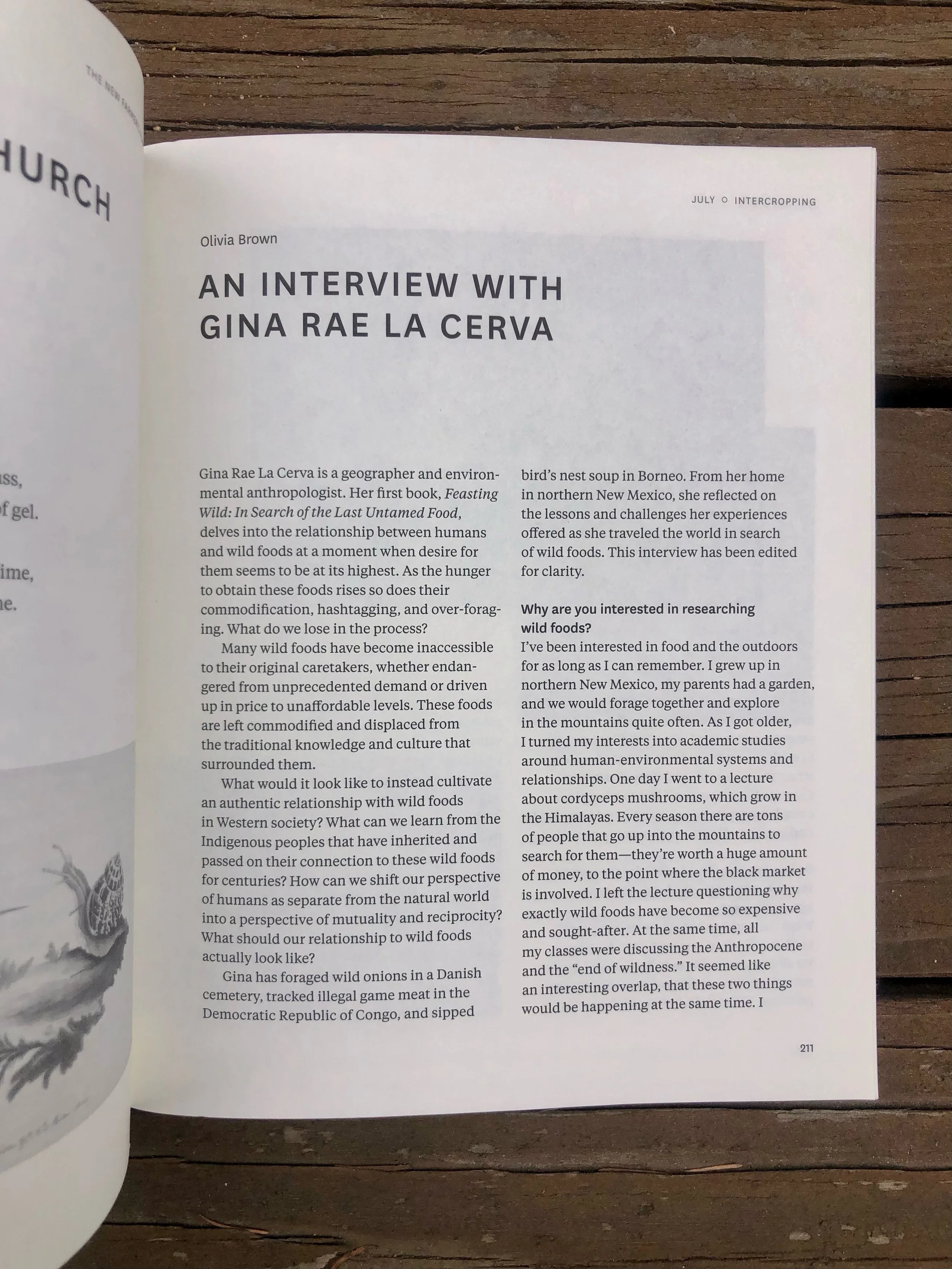

Written by Olivia Brown

An interview with Gina Rae La Cerva

Gina Rae La Cerva is a geographer and environmental anthropologist. Her first book, Feasting Wild: In Search of the Last Untamed Food, delves into the relationship between humans and wild foods at a moment when our desire for them seems to be at its highest. As the hunger to obtain these foods rises so does their commodification, hashtagging, and over-foraging. What do we lose in the process?

Many wild foods have become inaccessible to their original caretakers, whether endangered from unprecedented demand or driven up in price to unaffordable levels. These foods are left commodified and displaced from the traditional knowledge and culture that surrounded them. What would it look like to instead cultivate an authentic relationship with wild foods in Western society? What can we learn from the Indigenous peoples that have inherited and passed on their connection to these wild foods for centuries? How can we shift our perspective of humans as separate from the natural world into a perspective of mutuality and reciprocity? What should our relationship to wild foods actually look like?

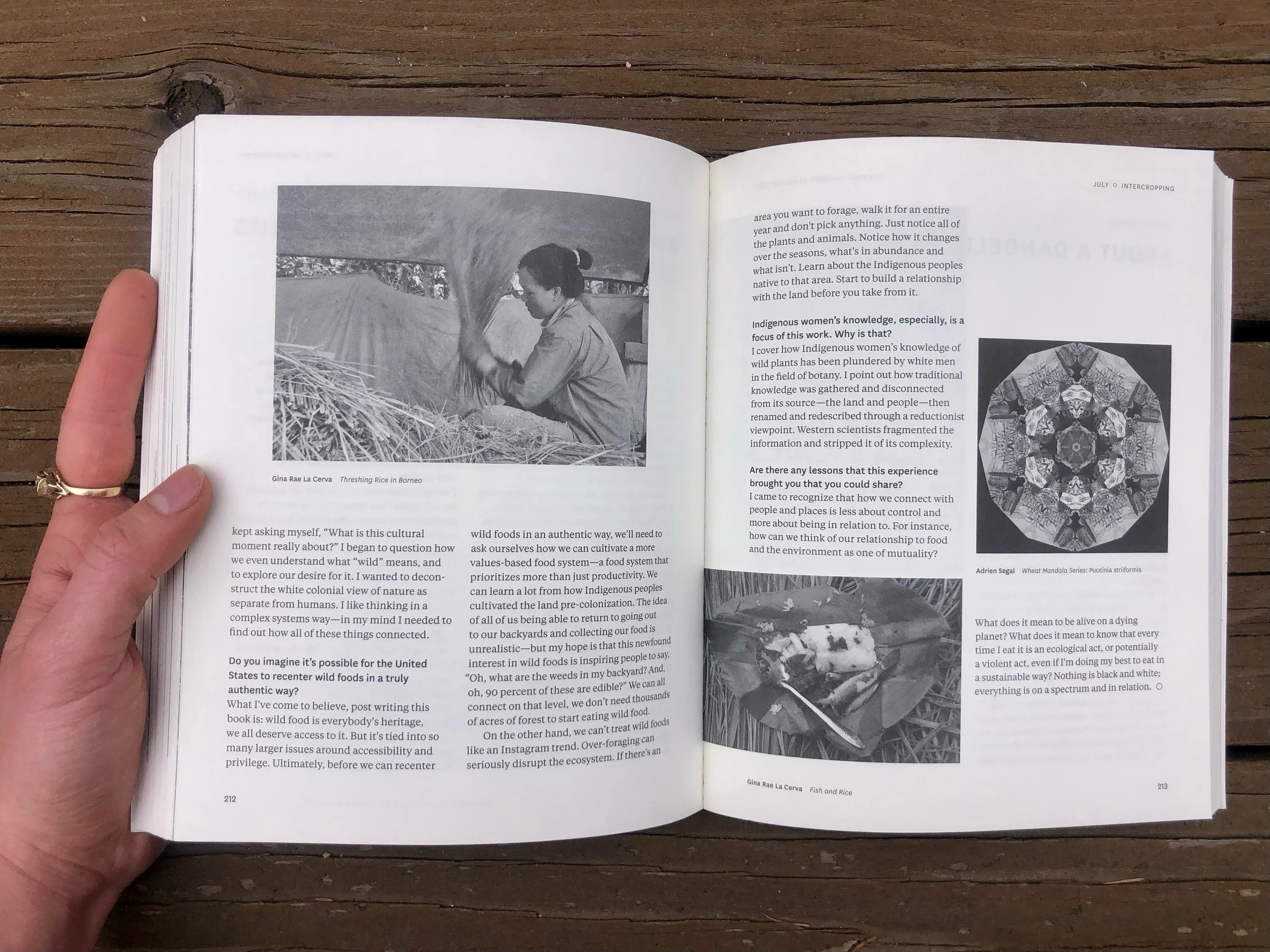

Gina has foraged wild onions in a Danish cemetery, tracked illegal game meat in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and sipped bird’s nest soup in Borneo. From her home in northern New Mexico, she reflected on the lessons and challenges her experiences offered as she traveled the world in search of wild foods. This interview has been edited for clarity.

Why are you interested in researching wild foods?

I’ve been interested in food and the outdoors for as long as I can remember. I grew up in Northern New Mexico, my parents had a garden, and we would go foraging together and explore in the mountains quite often. As I got older, I turned my interests into academic studies around human-environmental systems and relationships. One day I went to a lecture about cordyceps mushrooms, which grow in the Himalayas. Every season there are tons of people that go up into the mountains to search for them—they’re worth a huge amount of money to the point where the black market is involved. I left the lecture questioning why exactly wild foods have become so expensive and sought-after.

At the same time, all my classes were discussing the Anthropocene and the “end of wildness.” It seemed like an interesting overlap, that these two things would be happening at the same time. I kept asking myself, “What is this cultural moment really about?” I began to question how we even understand what “wild” means, and to explore our desire for it. I wanted to deconstruct this white colonial view of nature as separate from humans. I like thinking in a complex systems way—in my mind I needed to find out how all of these things connected.

Do you imagine it’s possible for the United States to re-center wild foods in a truly authentic way?

What I've come to believe, post writing this book is: wild food is everybody's heritage, we all deserve access to it. But it's tied into so many larger issues around accessibility and privilege. Ultimately, before we can re-center wild foods in an authentic way, we’ll need to ask ourselves how we can cultivate a more values-based food system—a food system that prioritizes more than just productivity. We can learn a lot from how Indigenous peoples cultivated the land pre-colonization. The idea of all of us being able to return to going out to our backyards and collecting our food is unrealistic—but my hope is that this newfound interest in wild foods is inspiring people to say, “Oh, what are the weeds in my backyard? And, oh, 90 percent of these are edible?” We can all connect on that level, we don’t need thousands of acres of forest to start eating wild food.

On the other hand, we can’t treat wild foods like an Instagram trend. Over-foraging can seriously disrupt the ecosystem. If there's an area you want to forage, walk it for an entire year and don't pick anything. Just notice all of the plants and animals. Notice how it changes over the seasons, what's in abundance and what isn't. Learn about the Indigenous peoples native to that area. Start to build a relationship with the land before you take from it.

Indigenous women’s knowledge, especially, is a focus of this work. Why is that?

I cover how Indigenous women’s knowledge of wild plants has been plundered by white men in the field of botany. I point out how traditional knowledge was gathered and disconnected from its source—the land and people—then re-named and re-described through a reductionist viewpoint. Western scientists fragmented the information and stripped it of its complexity.

Are there any lessons that this experience brought you that you could share?

I came to recognize that how we connect with people and places is less about control and more about being in relation to. For instance, how can we think of our relationship to food and the environment as one of mutuality? What does it mean to be alive on a dying planet? What does it mean to know that every time I eat it is an ecological act, or potentially a violent act, even if I'm doing my best to eat in a sustainable way? Nothing is black and white; everything is on a spectrum and in relation.